Category: News Articles

The Evolution of Innovative Approaches to Build More Secure and Safer Public Spaces

This presentation will outline and assess a number of trends, tensions and fault-lines that have characterised shifts over time in the design and regulation of safe public spaces across Europe and beyond. We do so to stimulate debate and discussion about the trajectory of learning and the challenges for the future. In doing so, we will draw from the wider Review we are conducting for the IcARUS project.

Background

European cities face significant challenges and major threats, such as terrorism and organised crime, but also incivilities, petty crime and new health risks, which all affect citizens’ feeling of safety. These challenges undermine the vibrancy and security of urban public spaces and threaten the well-being of European urban populations. In the context of fears of immigration, increased hyper-diversity, growing social and economic polarisation, the privatisation of public space and ‘splintering urbanism’ (Graham and Marvin 2001), Stuart Hall’s (1993; 2017) clarion call that how we develop ‘the capacity to live with difference’ is the central question of our time, remains as prescient as ever.

- Public spaces are places of difference, excitement, spontaneity, play and even unpredictability, where diverse populations come together, co-exist and interact in uncertain encounters (Sennett 1992). This is what Massey (2005: 181) refers to as the ‘throwntogetherness’ of public spaces. They combine co-presence and physical proximity with relative anonymity.

- Public spaces are contested places infused with different and competing economic and social and organisational interests, where commercial and business imperatives converge with moral claims over appropriate behaviour and conditions of citizenship.

- Security is but one imperative in public spaces that sometimes collides with other public goods or private pursuits.

- Use of public space fosters perceptions of safety. Underused and desolate public spaces are fear inducing (Jacobs 1961). Unlike other public goods (where the more others use it the less value it has for the individual), public space does not suffer congestion and crowding in the same way, such that a certain level of use is beneficial to all. Nonetheless, there are tipping points at which public spaces become over-crowded or dominated by certain groups rendering them less welcoming to others (Low 2017).

- In recent decades, many city authorities have sought to render public spaces safe through various modes of crime and terrorism prevention and order maintenance, but in so doing risk turning them into sterile, sanitised and (over-)securitised fortresses (Koolhaas, et al. 1995; de Cauter 2005).

- Public spaces are crucial arenas in which encounters with difference are hosted in convivial ways fostering civic norms that bind loosely connected strangers in mutual recognition (Barker, et al. 2019).

- The challenge is how public spaces can remain liberating and liminal yet safe, welcoming and regulated.

Tendencies, trends and learning across time

We propose that four broad tendencies and four emergent trends are apparent across time:

- A tendency to import overly crude versions of crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) strategies and ‘defensible space’ ideas that sought to alter the built and physical environment so as to ‘design out’ criminogenic opportunities; often infused with logics of ‘preventive exclusion’, opportunity reduction and overt surveillance as deterrence, and with little regard to aesthetics (Crawford 2009).

- A tendency to search for universal solutions under the banner of ‘what works’ which has drawn attention away from the situated and contextualised features of local places – with less attention to ‘what works’, ‘where’ and ‘for whom’? And simultaneously with little regard to which groups of people benefit from particular interventions or design features in a particular place/situation at a specific time?

- A tendency to prefer technological solutions – i.e. hardware – to human solutions in regard to addressing security concerns, with less concern for the intersection between social and technological processes.

- A tendency to over prioritise security as against other benefits, uses and values of public spaces – social, cultural, environmental, educational and health-related – resulting in the over-securitisation of public spaces. One of the ironies of such quests for security is that in their implementation they may foster perceptions of insecurities by alerting citizens to risks, heightening sensibilities and ‘scattering the world with visible reminders of threats’ (Zedner 2003: 163).

- A trend towards a cross-fertilisation and transfer of design and regulatory strategies first implemented in privately-owned public spaces – shopping malls, amusement parks, recreational facilities, etc. – where commercial logics frequently take precedence over overt securitisation (Crawford 2011).

- A trend towards a ‘process of naturalisation’, whereby regulation becomes embedded into the physical infrastructure and social routines in ways that is less noticeable, and a dynamic of ‘quaintification’ by which forms of regulation and control that are too harsh to fade into the background ‘are symbolically rehabilitated as both unthreatening and even laudatory’ (Flusty 2001: 660).

- A trend away from resort to coercive law enforcement, police, prosecution and punishment, towards compliance strategies that decentre the police and engage informal actors, civil society mediators and forms of persuasion, self-regulation and capacity building (Barker 2017).

- A recent trend towards human-centred solutions that are sensitive to local context, the causes of social problems, the nature of social interactions and early intervention.

Case Studies as Illustrations

We will illustrate how some of these trends and tensions have played out in practice and through learning across time with case study examples from two cities involved in the IcARUS project: Rotterdam and Stuttgart.

Example 1: In the city of Rotterdam, the City Marine programme has provided an innovative institutional mechanism for organising and delivering urban security. City Marines (Stadsmarinier) are individuals who are assigned to neighbourhoods determined to be most at risk (on the basis of data from the Safety Index). The task of the Marines, aided by a specific budget and resources, is to address serious issues within the community while also addressing the overall feelings of safety within the neighbourhoods.

- Youths were causing issues during New Year’s Eve celebrations in the neighbourhood of Bloemhof in Rotterdam including smashing windows, challenging police, and general disruption. This resulted in negative and unwelcoming feelings within public spaces for this community. Businesses were concerned about damage to their property and residents were less inclined to use such public spaces. The initial proposal for this issue included investing in more police/security presence and surveillance technology. This would have ultimately cost the city more and may not have created a feeling of a safe and welcoming community space.

- The solution devised by City Marine Marcel van der Ven approached this issue by speaking directly with ringleaders and creating a programme which benefited all within the community, and resulted in a self-regulating community. The City Marine was able to create a unique solution by understanding the neighbourhood, and those that live in it. He was able to tackle the underlying issues and improve the situation for all involved, instead of simply focusing on the security aspect of the issue. His versatile position as a city marine also allowed him to operate as a figure of authority, while not representing a police authority – thereby allowing him to establish and maintain a working relationship with those individuals who may be untrusting of police. This practice also became used in other neighbourhoods in Rotterdam.

Example 2: Stuttgart experienced multiple public order incidents since 2019, including riots in Stuttgart city centre, the latter being related to pent-up demand to gather and socialise post-lockdowns, and the associated mistrust in the authorities heightened by Covid-19 restrictions.

- These incidents are illustrative of contested uses of public spaces. Gatherings of large groups of young people, coupled with excessive noise and littering impacts on others’ enjoyment of these spaces, and can increase feelings of insecurity. The association of these incidents with young people from migrant backgrounds means youths are increasingly being stigmatised by other users of these spaces, polarising society.

- The city introduced Respektlotsen (respect guides/pilots) in 2020 with the aim of promoting tolerance by engaging mainly young people in casual, friendly conversation. The idea is to highlight that mutual respect can break down barriers, thus preventing conflict and aggression. Using informal actors who are sensitive to the local context (many of whom are from migrant backgrounds themselves) encourages youths to self-regulate their behaviour (non-coercive compliance), as well as opening avenues of communication with other users of public spaces, fostering integration.

- The interconnectedness of different urban security concerns is highlighted in Stuttgart’s approach of creating safer and more enjoyable public spaces facilitating co-existence, demonstrating the importance and value of incorporating human solutions, in addition to design and technology.

Future challenges

Rather than asking how ‘to build (ever) more secure and safer public spaces’ (as the title of this presentation suggests!), we should perhaps be exploring ways to ensure a minimum threshold of security that enables other civic values, social pursuits and public goods to flourish; where regulation is parsimonious and non-intrusive in ways that, wherever possible, foster self-regulation by citizens.

This requires us to see security as a foundational good; one that can also easily reach a tipping point that intrudes on other – more fundamental – social goods. It also necessitates an understanding of the diversity of uses and effects of public spaces as dynamic places; not as abstractions – as always virtuous or ever-malign – but as having meaning through the ways they are used in everyday human interactions and the way they relate to the wider cultural environment and economic forces of the city in which they are located.

Some key questions for the future remain:

- Restrictions introduced during the Covid-19 pandemic have impacted public spaces in new and particular ways, with the imposition of curfews, lockdowns and ‘stay local’ orders. To what extent has the experience of regulating public spaces during Covid-19 compounded or confounded existing trends and tensions? Has Covid-19 accentuated cumulative learning or prompted new departures?

- Environmental change has already become a major force propelling migration and displacement across the world, prompting ‘climate refugees’ scarcity of goods/resources. As such, global warming is likely to exacerbate the existing and growing geography of inequality and the uneven distribution of lived insecurity. How will public spaces adapt to the environmental needs and demands prompted by climate change? How will the new risks, harms and vulnerabilities fostered by global warming and the extreme weather conditions that accompany it impact on public spaces as key elements in city-wide ‘green infrastructures’ within European cities?

- In the face of fiscal restraints on municipal authorities and in the face of pronounced dynamics of privatisation and residualisation of urban public space and the growth of quasi-public ‘mass private property’ (Barker, et al. 2020), what futures do public spaces have as well-resourced, vibrant and convivial spaces? Can public spaces as civic resources survive the encroachment and commodification of the market?

References:

Barker, A. (2017) ‘Mediated Conviviality and the Urban Social Order: Reframing the Regulation of Public Space’, British Journal of Criminology, 57(4): 848–866.

Barker, A., Crawford, A., Booth, N. and Churchill, D. (2019) ‘Everyday Encounters with Difference in Urban Parks: Forging ‘Openness to Otherness’ in Segmenting Cities’, International Journal of Law in Context, 15: 495–514.

Barker, A., Crawford, A., Booth, N. and Churchill, D., (2020) ‘Park Futures: Excavating Images of Tomorrow’s Urban Green Spaces’, Urban Studies, 57(12), 2456–2472.

Crawford, A., (ed.) (2009) Crime Prevention Policies in Comparative Perspective, Cullompton: Willan.

Crawford, A. (2011) ‘From the Shopping Mall to the Street Corner: Dynamics of Exclusion in the Governance of Public Space’, in A. Crawford (ed.) International and Comparative Criminal Justice and Urban Governance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 483-518.

De Cauter, L. (2005) The Capsular Civilization: On the City in an Age of Fear, Rotterdam: NAi Publishers.

Flusty S. (2001) ‘The Banality of Interdiction: Surveillance, Control and the Displacement of Diversity’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 25(3), 658-64.

Graham, S. and Marvin, S. (2001) Splintering Urbanism, London: Routledge.

Hall, S. (1993) ‘Culture, community, nation’, Cultural Studies 7: 349–63.

Hall, S. (2017) The Fateful Triangle: Race, Ethnicity, Nation, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Jacobs, J. (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities, New York: Random House.

Koolhaas, R., Mau, B., Werlemann, H. and Sigler, J. (1995) S, M, L, XL, Rotterdam: 010 Publishers.

Low, S. (2017) Spatializing Culture: The Ethnography of Space and Place, London: Routledge.

Massey, D. (2005) For Space, London: Sage.

Sennett, R. (1992) The Conscience of the Eye: The Design and Social Life of Cities, New York: WW Norton & Co.

Zedner, L. (2003) ‘Too Much Security?’, International Journal of the Sociology of Law, 31, 155–84.

Engagement and Communication: An update on the State-of-the-Art Review

Engaging and communicating with partners and stakeholders is crucial for any project, so we were thrilled to have the opportunity to meet our IcARUS partners in person for the first time at the recent Security, Democracy and Cities Conference in Nice. One of the things that makes IcARUS distinct from other projects is the incorporation and synthesis of a large body of academic research and practitioner knowledge developed over the past 30 years in a State-of-the-Art Review. Immediately before the Efus conference, we were invited to engage with a new audience, delivering the keynote speech at the PACTESUR third annual meeting on 19th October, also in Nice, bringing together some preliminary insights from the State-of-the-Art Review with our ongoing discussions with partners.

The State-of-the-Art Review will form the foundation upon which our IcARUS partners move forward, incorporating the broad lessons learnt in developing and co-designing innovative and useful tools for cities to apply in a way that fits their unique needs. The context within which these processes work vary widely between our partner cities, and over the recent months we have been conducting follow-up interviews with them to gain better insight into the urban security initiatives and measures which operate within their cities. This is complimented by further interviews with various prominent international urban security experts, which has helped to ensure a well-rounded understanding of the evolution and current state of urban security.

Some key themes have emerged from our interviews. Indeed, many of these are strongly reflected in Efus’ PACTESUR project. We were extremely privileged to have the opportunity to present the keynote speech ‘The Evolution of Innovative Approaches to Build More Secure and Safer Public Spaces’, which was well received and helped stimulate a lively debate. This presentation features some preliminary insight on our work on the State-of-the-Art Review and our ongoing discussions with partners.

The presentation offers insights not only into one of the IcARUS project’s priority areas, namely ‘designing and managing safer public spaces’, but also highlights the interconnectedness of different urban security concerns faced by many European cities. It also reports on innovations in a couple of our partner cities (Rotterdam and Stuttgart) that illustrate some of the broader themes identified. A summary of our presentation can be found here.

IcARUS Panel Session at the European Police Congress in Berlin

The European Police Congress is an international conference organized by “Behörden Spiegel”, a leading German newspaper for public authorities, that represents a stage for decision-makers, police forces, and security authorities and industries. Held in Berlin, the congress is the platform whereby the dialogue between these actors is enhanced, and it allows for establishing contacts among colleagues from all over the globe. The conference is also a place for discussion regarding the main security concerns for Europe, such as migration, extremism, cyber threats, and many others. Hence, it is also a stage for political figures such as European ministers, economists, and executive-level representatives.

The Police Congress hosts discussions upon relevant security topics and issues while giving the chance to the industry to present the latest solutions and technologies in the field of safety and security. Within the EU, the Berlin Congress is the largest conference for internal security: it welcomes around two thousand experts from more than twenty Countries. Usually, it takes place every year but had recently been postponed due to the pandemic restrictions. The 24th edition of the Police Congress took place on the 14th and 15th of September 2021, in-person, and with all the necessary COVID prevention measures.

Here, among the several interesting panel sessions held at the Congress, one was inspired by the IcARUS project and featured some of the project partners. Erasmus University, the European Forum for Urban Security, the municipality of Rotterdam, and CAMINO joined on stage some representatives of the private industry (AIRBUS, and Smiths Detection, as part of the European Organization for Security) to hold a panel discussion upon “Smart Tools for Urban Safety: the co-production of public policy by private and public players”. This session focused on developing discussions and relevant points about how private parties, municipalities, and law enforcement agencies can better cooperate for a more efficient service and for more secure and safer cities. Panelists shed a light upon what the main safety challenges are, what approaches are best suitable, what technologies are in place for specific threats, and how the cooperation among actors is paramount for the delivery of public security. This diverse panel composition, and the extremely fruitful discussions from the audience, led to the conclusion that it is exactly the joint tetra-effort of public sector, private sector, academia, and civil society organizations that can result in better informed decisions for public security policies. It is this dialogue among actors that needs to be fostered for an even better secure and safer Europe. A concept that is indeed shared at project level, and that the consortium, while collaborating fiercely, is furthering.

Do you speak IcARUS? Why the project has created a common glossary of terms

The IcARUS consortium is large and varied, gathering 6 municipalities and 11 institutions from 11 countries as well as an Expert Advisory Board and a Consultative Committee of Cities. Each partner has knowledge and experience of urban security issues but at varying degrees and obviously in different circumstances. Does juvenile delinquency for example – one of the project’s four focus areas – have the exact same meaning in Greece, the UK, Germany or Spain?

The consortium thus decided early on that one of the first things to do was to agree on the meaning of the project’s key terms and make sure everybody is speaking of and working on the same things. This goes well beyond the definition of terms per se. Behind the words and the meaning we give them lies a whole philosophy, a way to frame issues and clues as to how to tackle them. For example, when we speak of managing public spaces, do we mean relatively simple things such as providing public benches or ensuring that there are no physical obstacles to the flow of pedestrians, or do we mean in a much broader sense managing a city’s public spaces so that they contribute to social cohesion? Ask the question to a group of local authorities, academics, private businesses and civil society organisations and you are sure to fire a rich debate.

A creative and learning process

The IcARUS project did just that in a process that was driven by the University of Leeds. Over a period of about three months, they analysed academic publications in order to define a common meaning for:

- the project’s four focus areas: preventing and reducing juvenile delinquency, radicalisation and organised crime as well as managing public spaces;

- a series of cross-cutting themes: governance and diversification of actors, cyber/technology, gender issues, and transnational and cross-border issues;

- three key terms and expressions: urban security, crime prevention strategies, and multi-stakeholder partnerships.

They proposed a series of carefully argued definitions, which were then submitted to the project’s consortium and fine-tuned through a series of back-and-forth feedback. Apart from producing a glossary that will be used by the partners during the duration of the project, this process fostered dialogue among professionals who do not usually communicate much, or at least not on such conceptual issues, and was thus fruitful as such.

Indeed, it reflected the co-production process that IcARUS and Efus advocate for urban security policies and actions, which brings together local stakeholders from diverse backgrounds. Creating the glossary was in itself a ‘multi-stakeholder approach’ and thus gave the partners, in particular the six municipalities, ideas on how to do this concretely when dealing with urban security issues at home. Also, the process itself mirrored the Design Thinking methodology used throughout the IcARUS project in order to produce innovative solutions to urban security problems based on the end-users’ real needs.

Design Thinking virtual training workshops: A fun and fruitful experience

The IcARUS project organised in March its first training on the Design Thinking Methodology. Over a period of four days, 56 representatives of the project’s partners took part in the training sessions, which combined team and individual work, brainstorming and interactive games.

By the end of the training, the partners were familiarised with the novel techniques of the DT methodology, and eager to adopt them in their own organisational settings.

The IcARUS project organised in March its first training programme on the Design Thinking methodology. Combining team and individual work, brainstorming, and interactive exercises in the form of games, the four sessions were given online. The training started off with providing the attendees with the general guidelines and specific examples of the methodology at hand, so that they could understand the reason why ‘thinking outside the box’ is an efficient way to solve urban security problems. Participants then shared real-life situations they encounter in their work in relation with solving problems within the urban environment. They were then asked to discuss real-life situations related to the four IcARUS focus areas (i.e. juvenile delinquency, radicalisation, trafficking and organised crime, and the design and management of safe public spaces). As they gained a better grasp of the Design Thinking methodology, they were asked to co-create a DT process by experimenting on real examples of urban criminality.

The last two training sessions focused on the four competences needed to successfully implement the methodology, which are interconnected: empathy, experimentalism, creativity, and collaboration. Four sub-groups were formed, one per competence, where participants had ample opportunity to contribute and interact with the rest of the team.

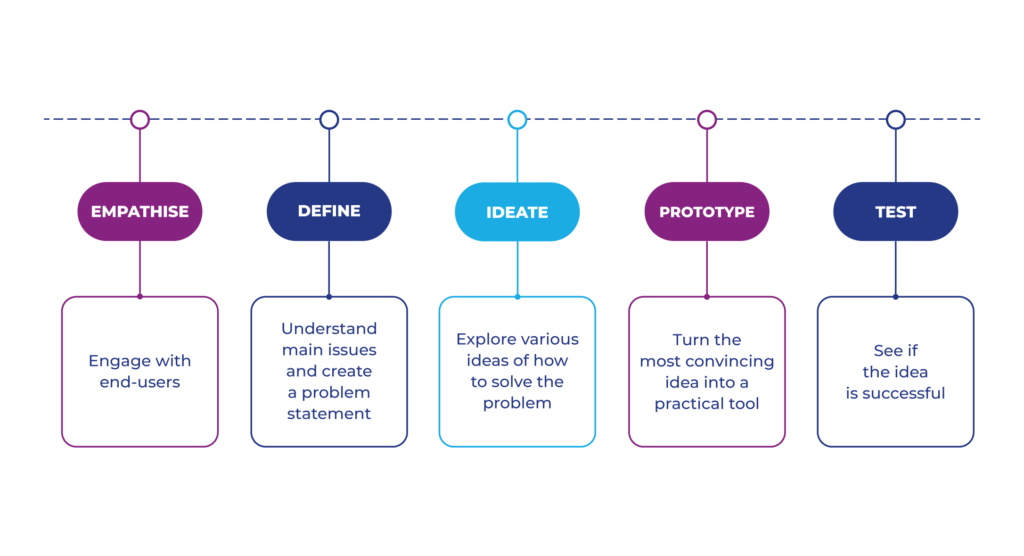

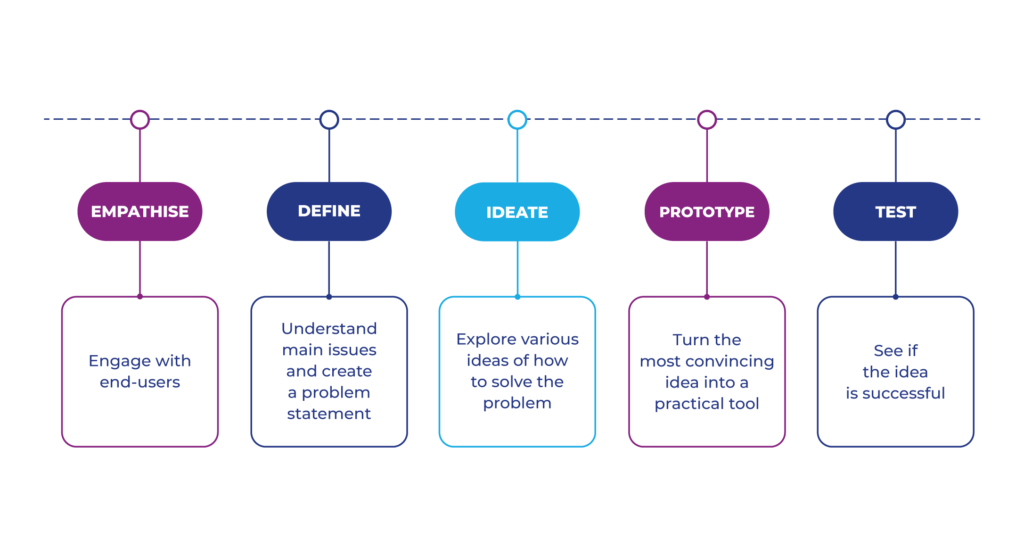

An overarching aim of the sessions was to effectively demonstrate the five Design Thinking stages (see figure below) while co-creating an innovative ecosystem. To that effect, the trainees were given insight on when, how, and why to apply the Design Thinking approach, the pros of generating ideas through empathy, ways to determine and understand stakeholders, how to create the necessary strategies to address a problem, when to prototype and test said strategies, and how to compare the ideas produced through this process in order to decide on an optimal, functional solution.

The training was met with enthusiasm on the part of the trainees, proven by their active participation and fruitful exchanges throughout the sessions.. Many participants said afterwards that they now embraced the Design Thinking process and were provided with the necessary roadmap to facilitate their navigation throughout the rest of the IcARUS’ workshops. All sessions were interactive, dynamic, and entertaining, with the sub-group sessions being the most productive due to their small number of participants and the focus on problem-solving connected to real-life situations, which were tailor-made for each competence.

Lastly, it should be noted that the focal point of the sessions’ success was that it managed to build trust, foster connections, and create a bond among the different members of the consortium. To that effect, the participants communicated feelings of being inspired by the training sessions and satisfied with the group dynamic that had been created. Many also agreed that they had a very enjoyable experience.

How IcARUS is leading innovation for urban security

“Think outside the box” is easier said than done. Imagine finding a method that allows you to have innovative ideas and then to actually put them into practice. Imagine following a methodology proven to be successful. Imagine an approach that allows you to collaborate and interact with a diverse team of experts, while delivering new ideas. Imagine facing tough societal issues with inventive tools built to overcome them. Now don’t just imagine: read here how we are doing this.

The scope of the IcARUS project is ambitious and the urban problems it aims to tackle are quite challenging. Our project’s goals include finding adequate and successful tools to face problems related to urban security and crime prevention initiatives. IcARUS encompasses the prevention of juvenile delinquency, prevention of radicalisation, the security of public spaces, and the prevention of trafficking and organised crime. These topics are certainly quite sensitive and challenging. This is why the project needed a strong methodology that would allow partners to formulate new and innovative ideas to then shape tools and address those problems. Hence, IcARUS has adopted Design Thinking, a methodology born within the private sector that ensures fruitful co-creation and cooperation among actors for delivering new solutions to long-existing problems.

Design Thinking is a methodology that comprises several steps and envisions different players interacting with each other. The IcARUS project has a diverse pool of partners, each bringing its own expertise and resources. In order for Design Thinking to lead to innovative and effective solutions, diversity in players is paramount. Furthermore, participants must follow determined steps that help them co-build alternative solutions and tools. These steps are: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test. This means that actors need to fully understand the ultimate beneficiaries of the proposed solutions; they need to concisely delineate the root issue to be tackled; they must collect all the possible ideas the group can come up with; they then choose one, and finally they will test it by applying it. Interestingly, these steps, or phases, are not necessarily to be followed in this order. After testing the final prototype, for instance, the group can experience negative feedback and go back to the ‘ideate’ phase. Or if they find that the fault is a lack of empathy, then designers should go back to the very first phase.

Design Thinking places end-users at the core of the discussion and makes designers look at the problem through the lens of end-users. Designers should put themselves in the shoes of end-users to see exactly where the problem lies and how to best address it. This is what we had in mind when drafting the IcARUS guidelines: we aimed at assisting partners in their journey throughout the project. The IcARUS guidelines are specifically intended for allowing designers to best use Design Thinking and to strictly follow the main principles of such approach. We divided the set of guidelines into sub-groups to tailor them to the group’s specific needs throughout the project. Partners have been following these guidelines for the first time during the recent training sessions, where they got familiarised with the methodology and could first experience what it means to co-create and how to best formulate an innovative solution. So far, training sessions have been a success and partners are ready to apply Design Thinking to the workings of the project. Hence, great ideas are coming up and interesting solutions are on the horizon. Stay tuned.

Consultative Committee of Cities Interview – Werner Van Herle

What does the city of Mechelen hope to bring to the IcARUS project?

Werner Van Herle, Head of the department for Prevention and Public Safety, City of Mechelen and member of the Consultative Committee of Cities: Mechelen understands and believes that urban safety is about what people need in order to be secure, feel safe and to enjoy their fundamental freedoms and rights. Local governments have an important responsibility in providing a safe environment for all residents. For over 20 years, the City of Mechelen has been investing significantly in an integrated urban safety and security programme. Innovation, experimentation and thinking out of the box are highly valued and key elements of our local strategy. We have quite some experience in developing new answers to challenging urban security threats, in particular regarding the four areas covered by the IcARUS project, which we are keen to share with the project partners.

What results do you expect from IcARUS?

Our expectations are high because the ambitions of IcARUS are high: custom-made solutions to security challenges through social and technological innovations. The project gathers an interdisciplinary group of motivated experts who will be working together to achieve this ambition. This will create a unique learning environment in which we will find inspiration in order to fine-tune our local security approach.

What is the added value for your city of being part of the consultative committee of cities (CCC)?

We are greatly honoured to be part of the project’s Consultative Committee of Cities (CCC), especially given the fact that we are a small/mid-scale city as per European norms. As members of the CCC, we are part of the IcARUS consortium and will thus follow its work and results. It will also enable us to expand our international network and to be in contact with experts from other EU cities.

What other cooperation opportunities can arise from your involvement in this project?

Mechelen is part of the Partnership on the security of public spaces of the Urban Agenda for the European Union. We are coordinating action 5 on the measurement of social cohesion and how it affects urban security. In that respect we want to create a common method for local security managers to measure the impact of existing local social cohesion projects on real or perceived insecurity. A second objective is to provide a new perspective to find new solutions for complex social or insecurity issues by exploring the possibilities of the ‘Collective Impact Model’ – a framework for achieving large-scale systems changes in communities through coordinated multi-sector collaborations –, in an EU context. In other words, there are many links and synergies between the work carried out in the frameworks of the Urban Agenda and of IcARUS. Sharing this work might open interesting opportunities.

Expert Advisory Board Interview – Dr. Barbara Holtmann

What do you hope to bring to the IcARUS project?

Dr Barbara Holtmann, Director of Fixed Africa and member of the Expert Advisory Board: I feel very privileged to be a part of the IcARUS project. Too often we are stuck with terms of reference that require us to replicate interventions and programmes that have delivered evidence, regardless of how sustainable or replicable they might be. Innovation is essential to making cities safer and that requires courage. This project has courage embedded in its DNA and I believe that I can offer both insight into innovative practices and support the analysis of findings that allow for greater creativity and possibility. I am a natural collaborator and I am deeply curious – I hope this means I can help dig deeper and enable inclusive design and management of promising practices.

What do you expect to take away from the project?

The thing I love most about my job is that it offers new and different exposures and experiences – with new challenges. To have the time and space to get to know practitioners, to better understand some of the challenges and to learn together new ways to overcome them, or in some cases, how best to live with confounding variables and intractability is something that excites and motivates me. I hope I will come away with new friends and colleagues, new ideas and a whole load of new learning.

In your opinion, what is the most innovative aspect of the IcARUS project?

Being open to innovation is as innovative as a project can be and it seems to me that this is its core characteristic. The project design expects real value at so many different levels and from so many different sources. Its duration also responds to a reality that is often missed; change takes time and there has to be space to err and amend and shift and regroup. It is rare to be involved in a project where these things are acknowledged.

How can the expected outputs of the project be impactful?

The outputs of the project will provide cities, policy makers and practitioners with new tools. There is an openness to the project that offers wide inclusion in what is found, done and delivered. It is only through this kind of approach that real systemic change can be made. The layers of consultation and collaboration will encourage widespread uptake of lessons and tools and it is in this spirit that real learning occurs.

Framework of Rules of Ethics of Criminological Research. In the light of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

Since the implementation of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2016, creating a framework of rules of ethics of criminological research has become more important than ever. Christina Tatsi, lawyer and PhD in Criminology from Panteion University, reviews a new book on this subject recently published by her University, Framework of Rules of Ethics of Criminological Research. In the light of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Key concepts of data protection

The book is prefaced by reputable scientists with special knowledge and experience in this field, such as Calliope Spinellis, Emeritus Professor of Criminology at the Law School of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA), Maria Kranidioti, Assistant Professor of Criminology at the Law School of NKUA and Evangelia (Lillian) Mitrou, Professor at the Aegean University in the Department of Information and Communication Systems Engineering, who present important concerns and ethical issues that arise in criminological research.

The authors start by setting out the institutional development of data protection from the first attempts to secure the right to privacy to the implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation (2016/679/EU-GDPR).

They explain the key concepts defined in Article 4 of the GDPR such as “personal data”, “processing”, “pseudonymis ation”, and “consent”. They also outline general principles that researchers must bear in mind when conducting their research, such as “general rules on the security of the research”, “principle of legality, objectivity and transparency”, “the proportionality principle”, “confidentiality assurance”, “informed consent”, and principles applicable to minors, detainees, addictive substance users, etc.

Rules that researchers must abide by

The authors detail the rules that researchers must abide by when conducting their work, notably being professional, bound by their activities and enhancing the overall progress of the group. They must also uphold values of equality and respect.

One of the most important ethical obligations for researchers is the protection of intellectual property, which requires to properly reference their sources and references, including all authors.

Reference is also made to the violation of the research’s integrity. According to the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity, failure to observe good research practices, such as the construction of research results, the falsification or alteration of research material, and plagiarism, constitute a violation of professional duties. Scientific experts must therefore ensure that all ethical rules and the provisions of the legislation in force are complied with when the research is carried out. Conflicts of interest may arise, which may affect various aspects of a study. In this case, the researcher should be aware that any conflict of interest may negatively affect the research and also confirm that there is no conflict of interest regarding himself/ herself at the time of undertaking his/ her duties. At the same time, the research team has to manage this conflict.

Researching with real-life persons

The book’s third chapter, entitled ‘Ethical issues in research involving natural persons’, addresses information and consent, confidentiality and financial consideration.

The information and consent (informed consent) of the participants is an essential precondition for any scientific research that involves people as subjects. Participation in criminological research must be voluntary and the participants must give their consent once they have been thoroughly informed and have fully understood the scope of the research.

The question ofensuring confidentiality includes the concepts of anonymity and confidentiality. The researcher shall maintain confidentiality and protect the participant’s interests even when he or she does not understand the risk posed by the disclosure of his or her data. The principle of anonymity does not concern the researcher who collects the data, but rather any third party, while confidentiality concerns everyone.

Lastly, reference is made to financial compensation. The practice of providing financial compensation to participants as an incentive to participate in the research may alter their freedom of will and should therefore be avoided.

Research with vulnerable subjects

Another aspect examined by the book is what the authors call “Special research cases”, in particular research concerning minors, prisoners, users of addictive substances, victims of domestic violence, mentally ill patients and victims of human trafficking. When conducting such research, specific ethical issues may arise because of the particular characteristics of the groups mentioned. In these cases, greater attention is required concerning the disclosure of any personal data. Also, failing to understand the scale and results of the research can have multiple adverse effects on the lives of the individuals concerned compared to other segments of the population. Thus, except for the general principles which are applied to each survey, when it comes to conducting research on vulnerable groups of people and in particular cases, more specific approaches are required that must always be in compliance with legislation.

Processing personal data

The book includes a chapter on the processing of personal data, as well as on the rights of data subjects such as the right to rectification, to erasure (right to be forgotten) and to the restriction of processing. In addition, extensive reference is made to the conditions of third-party access to the participants’ personal data. This section of the book also sets out the measures to be taken by the controller and the processor regarding the security, privacy and anonymity of the research participants.

The last chapter of the book deals with the “Security of individuals and data”. There is extensive reference to the measures that researchers and participants must take and to the rules that must be followed while they are conducting the research, storing and securing the collected data. The possibility of damage (both physical and mental) should be prevented, and all necessary protection measures should be taken with respect to the dignity and rights of the participants. Meanwhile, data should be collected for specific purposes and processed in a way that guarantees its security. Reference is also made to the Data Protection Officer.

Various appendices and references

The book concludes with various appendices about the licensing process of research projects and the role of Research Ethics Committees. A number of forms are available to obtain authorisation to conduct research, as posted on the websites of the Panteion University, the National Centre of Social Research, the Democritus University of Thrace and the University of Crete. Lastly, a bibliography lists relevant legislative and ethical texts concerning the conduct of research.

> Framework of Rules of Ethics of Criminological Research. In the light of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), co-authored by Professor Christina Zarafonitou and Dr. Ioanna Tsigkanou in collaboration with the project team of PhD candidates Elli Anitsi, Katerina Kalafati-Michailaki, Penelope Kollia, Elena Syrmali and Christina Tatsi (who was also the project team’s co-ordinator). Published by Dionikos Publications as part of the series “Criminological Studies” by the Programme of Postgraduate Studies (MA) in Criminology of the Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences.

Urban Crime – An International Journal

Urban Crime – An International Journal is a new scientific journal published by the Laboratory of Urban Criminology of Panteion University in Athens. It presents a composite of analyses and syntheses of research at the intersection between crime and the urban environment, drawn from a variety of sources. With peer-reviewed, original research articles in English, French and Greek, it is a useful resource for academics and researchers from various disciplines.

Published by the Laboratory of Urban Criminology of Panteion University in Athens, Urban Crime – An International Journal includes reviews of new books and analyses and commentaries on current urban crime issues. The journal also occasionally publishes thematic/special issues with the participation of guest editors.

A useful new resource for academics and researchers

Urban Crime – An International Journal is a useful resource for academics and researchers from a variety of disciplines including, among others, criminology and criminal justice, sociology, social policy, social anthropology, geography, politics, economics, and cultural and media studies, as well as practitioners and policy makers. Its promoters ambition to turn it into a truly global publication that represents the diversity of thematic interests and research cultures in the field of urban crime studies.

The vision for the growth and impact of Urban Crime – An International Journal involves:

- Implementing rigorous and swift editorial and peer-review processes that will make the journal an indispensable forum in the field.

- Becoming a truly global publication that represents the diversity of thematic interests and research cultures in the field of urban crime studies. It will showcase cross-cutting, theoretically ambitious studies that are relevant across specialisations, and research that draws from wide-ranging geographical, cultural, political and social contexts. To this end, we intend to invite submissions from all parts of the world to further promote the journal not only in contexts that are well represented (e.g. Europe and North America) but also, through our extensive scholarly network, in regions such as Asia, Asia-Pacific, Africa and Latin America. These regions are currently under-represented and can offer fresh empirical and theoretical insights into the study of urban crime.

- Encouraging the submission of quality research and commentary by practitioners such as law enforcement agents, members of the judiciary, government and local government officials, industry and non-governmental organisations working on urban crime-related topics.

Two or three issues per year

The journal is published two to three times a year. The Editorial Board consists of Professor Christina Zarafonitou as Editor in Chief and eminent academics. All the processes are conducted in line with the journals’ code of ethics. The first issue was published in June 2020 and is available at https://ojs.panteion.gr/index.php/uc/issue/view/22

subscribe to be the first to receive icarus news!

Know what we've been up to and the latest on the European urban security frame.