Month: April 2023

Obtaining Feedback: A Key Component in Successful Stakeholder Participation

The activities in work package 3 of the IcARUS project are currently focused on tool development. This summer, the cities will present the final version of the developed tools to their civil society partners. In the coming months, tool validation workshops will take place in Lisbon, Nice, Riga, Rotterdam, Stuttgart, Turin. These validation workshops conclude the participatory development phase of the tools and should enable the cities to engage with their stakeholders and communities of interest. The collected feedback will be used in two ways: first, to generally validate the tool and inform the cities’ security strategies and second, for developing criteria for the implementation of the tool. Therefore, these meetings also represent a transition to the tool demonstration phase.

In a joint effort with the University of Salford, the Swiss research institute Idiap, EFUS, and other IcARUS partners, the six cities are each developing a tool in the priority areas of their choice: Lisbon and Turin on preventing juvenile delinquency, Stuttgart on preventing radicalization leading to violent extremism, Riga and Nice on designing and managing safe public spaces, and Rotterdam on preventing and reducing trafficking and organized crime. However, the collaborative approach in tool development is not limited to the IcARUS partners. Each city organized a local kick-off workshop in spring/summer 2022 to which a number of municipal and, most importantly, civil society stakeholders were invited. The goal was to discuss the respective security challenge in the city in more detail and to develop initial proposals for solutions following a design thinking methodology. The results of the workshops laid a first basis, and since then, the cities have been in a process of involving the partners in the tool development. Each city has done this in a different manner according to their needs, pace of progress, and possibilities, such as meetings with individual partners, group discussions, or events to present the design brief for the tool.

The preparation of the upcoming tool validation workshops in each city focuses on obtaining feedback from the participants. Together with the city representatives, Camino prepares these workshops and offers support in the form of training sessions on workshop facilitation. Apart from developing a workshop concept, the practical implementation of the events are planned, strategies for dealing with different forms of feedback are developed and tested.

Obtaining feedback is a key component in successful stakeholder participation and for the further collaboration with these partners in the area of urban security. Obtaining valuable feedback on the implementation of the tool is a necessary step to link the development phase to the demonstration phase within the project. In the IcARUS project, feedback is used for three aims:

– validating the tool

– developing criteria for implementation

– informing the cities’ security strategies.

Dealing with feedback was therefore a central part of the first training session organized by Camino in cooperation with the citizen empowerment organisation MakeSense and the cities. A key takeaway of this first session was: a serious feedback culture does not mean that all suggestions and requests can be met, whether it is about validating the tool or taking it into account in the security strategy. Therefore, it is important for workshop facilitators to be clear and transparent about what will be done with the feedback, what kind of feedback can still be taken into account for the implementation, and how feedback can inform other aspects of the municipal security strategy.

Even if feedback is sought for the validation of the tool, it is crucial that feedback is not collected pro forma, but that it feeds into the further process, e.g. implementation or more generally into the development of the cities’ security concepts. Otherwise, feedback as an approach to participation may be watered down to a form of “particitainment” (Selle 2011):

“Particitainment” is becoming widespread. Instead of substantial debate in the context of a lively local democracy, citizen participation is merely staged, it only suggests participation in opinion-forming and decision-making and can’t deliver on its promise. In fact, many of the results of these processes have no significant influence on urban development and do not change established dynamics in local politics and administration. More importantly: The inflationary staging of ineffective participation processes risks further promoting disenchantment with politics and planning processes and political apathy.” (Selle 2011, p. 3, own translation)

Ineffective participation may thus lead to a feeling of frustration and rejection of the whole participatory process. Concretely, within the context of the IcARUS project, ineffective participation might diminish acceptance for the tools developed by the project and be a burden for future civil society involvement. If participants had the sense that their opinion was only formally requested, they might end up feeling that their time was wasted. This issue should be considered, as the time factor is one of the barriers to participation in such settings.

However, if feedback on participants’ feelings, opinions and wishes is taken seriously, it is then possible to learn from their experience and encourage engagement and cooperation. This can contribute to strengthening a culture of citizen participation. It is also a positive approach to criticism and a productive way of dealing with failure or disappointment, which in turn has a positive effect on the resilience of cities and on their respective security strategies. This is what the tool validation workshops, and the preparatory processes organised in their run-up, will seek to achieve.

The participation process varies greatly in the 6 cities, which is not surprising. Participative cooperation must be established locally and in view of a specific context, and that takes time.

In addition to these considerations on the importance of communication within the tool validation workshops, another important topic of the first training session was to deal with emotions using the “Emotion Monster Cards”. This was useful for finding out how the city representatives feel about the upcoming workshops and what their expectations are. Next to feeling pressure to meet all of the expectations of their partners or fearing unpredictable obstacles, they are also excited to enter this phase, hoping for constructive feedback. Furthermore, through the participatory approach of tool development in the IcARUS project, the cities seek to strengthen their relationship with their local partners and to build new sustainable collaborations.

“Time and again, experts who oversee citizen participation in various communities, make a puzzling discovery: In one city or district, their offer of participation is met with a lack of interest or tiresome discussions with only a handful of the same ‘regulars’. In the next city or district however, the room is full, the discussions are lively and constructive and lead to useful results for the further planning process. How can this be explained? There are various hypotheses for the causes of these local differences. It is clear that it is not due to social structures (the different experiences are also made in neighbourhoods or cities with similar constituencies), nor is it due to the content or the manner of planning. It is also clear that this question needs to be addressed more systematically. Nevertheless, one aspect is already clear: communication skills and interest in exchange require (positive) experiences. We are thus moving in a circular, or rather spiralled, processes. Out of experience with successful exchange grows a willingness and an interest in further communication.” 1 (Selle 2011 , p. 16, own translation)

1Selle, Klaus: Particitainment. Oder beteiligen wir uns zu Tode? PNDonline III/2011, www.planung-neu-denken.de

Design Thinking out of the box to tackle complex urban problems

The IcARUS project is using the Design Thinking methodology on the development of tools which respond to local urban security challenges because it is proven to foster more innovative, citizen-friendly solutions to complex urban problems. One of the world’s foremost experts on Design Thinking, Professor Kees Dorst recently met with IcARUS partners during a web conference organised by Efus.

First conceived in the 1960s by designers seeking to better match customers’ needs and expectations when creating new products, the Design Thinking methodology is now used by private sector organisations all over the world. More recently, it has also gained ground in the public realm, inspiring innovative approaches to policy making.

A people-centred approach

The core principle of Design Thinking is to approach issues from the perspective of users. Applied to urban development and urban security, it means empathising with people and how they live and use their city, rather than through the mental construct that is, say, ‘social exclusion’, or ‘unemployment rates’. Simplified in the extreme, the idea is to go and listen to the people on the ground rather than being fixed on data. This empathetic approach often leads to discovering factors that do not appear in hard data, which in turn can inspire innovative solutions based on real life.

Fostering innovative local responses

Such a creative approach adapted to local urban security policy-making and can help local authorities to improve problem definition and understanding of how citizens experience security, which is why IcARUS seeks to disseminate it among European local authorities. Titled How can the design thinking contribute to a more strategic approach to urban security?, the web conference organised by Efus on 28 February, gave the IcARUS project’s partner cities a unique occasion to discuss ‘live’ with world-renowned expert on Design Thinking Professor Kees Dorst, who is Director of the Designing Out Crime Research Centre at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) (Australia).

Complex, dynamic and networked problems

In today’s globalised age, complex problems abound – from tensions in urban hotspots through to radicalisation, to the need to care for an ageing population. Drawing on his years of research into design practice and design thinking, Professor Dorst has developed a methodology he calls ‘frame creation’. In this clear, nine-step process, he demonstrates a method that first generates a deeper understanding of these difficult problems, and then reframes them in a way that leads to new solutions that work.

“Today’s problems are so complex, dynamic, and networked that they seem impervious to solution,” he says. “The trusted routines just don’t work anymore. These new types of problems require a completely different response.”1

1 This quote and the section sub-titled Complex, globalised problems is taken from an article published on University of Technology Sydney’s website, and signed by Jacqueline Middleton: https://www.uts.edu.au/about/faculty-design-architecture-and-building/news/new-thinking-resolves-complex-problems-design

Case studies in Sydney

In Australia, UTS and Professor Dorst have worked with public authorities to solve some of Sydney’s urban problems. During the web conference, he highlighted the case of the Kings Cross nightlife neighbourhood.

In the early 2010s, it had a bad reputation for alcohol-fuelled violence. The city authorities and police took a repressive response, including ‘lockout’ laws restricting alcohol sales. This led to the closure of some local businesses but didn’t stop antisocial behaviour and more serious problems.

The city thus decided to partner up with UTS’ Design Out Crime Centre, which took a radically different approach. Using the Design Thinking methodology, they looked at who was partying in Kings Cross at night: just well-meaning young people who could be anybody’s children. The problem was that when thousands of them all got out of bars and nightclub in the wee hours of the night, they had no transport back home, nowhere to sit and sober up, and nowhere to relieve themselves or charge their phone.

Like a music festival

The solution proposed was to treat the whole Kings Cross neighbourhood like a music festival, i.e., a place where there are large number of intoxicated people, but with more amenities and less incidents. The core aspects of festival management are Distraction (keeping crowds happy) and Extraction (getting them out).

Based on this analysis, transport services were improved to get people home faster, thus the area less crowded, and thus with less risks of violence flare-ups. Safe spaces manned by volunteers were set up where people could take a break and charge their batteries (both figuratively and literally), and where women could take refuge from sexual harassment. Clear signage was introduced in the whole neighbourhood (signs on the pavement and through lighting) to gently ‘nudge’ partygoers towards the exits and safe areas.

This approach contributed to significantly pacify Kings Cross for the enjoyment of both partygoers and local residents. It proved so successful that it inspired Sydney’s 17-year plan (2013-2030) to encourage nightlife as an economic opportunity, called OPEN Sydney.

Co-producing concrete solutions

The IcARUS six partner cities – Lisbon (Portugal), Nice (France), Riga (Latvia), Rotterdam (Netherlands), Stuttgart (Germany) and Turin (Italy) – are currently working on developing pilot projects based on Design Thinking to tackle issues they have identified as a priority in their local context.

Even though each city has distinct issues and characteristics, meaning that there are no fit-for-all solutions, the experience of Sydney with Design Thinking to solve their nightlife problem can be a source of inspiration. It shows how listening to citizens and thinking out of the box can lead to solutions that really work and don’t need to be overly expensive or complex.

> Read the IcARUS factsheet on the Design Thinking methodology

> Kees Dorst’s book, Frame Innovation – Create new thinking by design, is published by MIT Press

A Critical Analysis of International and National Legal Frameworks for Urban Security Policies

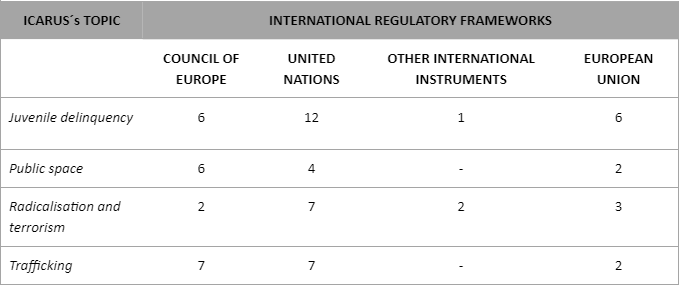

IcARUS is an EU-funded project that aims to identify innovative ways to implement urban security policies by addressing barriers to their implementation. The project focuses on four priority areas: preventing juvenile delinquency, preventing trafficking and organised crime, managing and designing safe public spaces, and preventing radicalisation leading to violent extremism. To clearly delimit the limits and possibilities of the IcARUS outcomes in ethical and legal terms, Plus Ethics has conducted a legal analysis of the international and European legal frameworks in the sector of crime prevention and urban security, as well as the national legal frameworks of six cities: Nice, Rotterdam, Riga, Stuttgart, Turin, and Lisbon.

To achieve the project’s objectives, the legal report (D6.1) adopted a methodological approach based on the analysis of regulatory frameworks at both the international and national levels. The project analysed the legal instruments available to the law enforcement agencies (LEAs) or municipalities in each of the six cities. The analysis focused on the relevant guidelines, recommendations, resolutions, directives, declarations, rules, protocols, conventions, proposals, opinions, and international codes at the international level. At the national level, the analysis focused on the constitution, criminal code, specific legislation, and other relevant instruments. To identify the specific urban security challenges faced by each city, an online questionnaire was distributed to representatives of each city.

Findings

Firstly, the analysis of the international legal frameworks at the Council of Europe, United Nations, and European Union levels revealed that the most relevant instruments for each of the priority areas are as follows (in quantity of instruments found):

On the other hand, the IcARUS project has collaborated with law enforcement agencies and municipalities in Nice, Rotterdam, Riga, Turin, and Lisbon to analyse legal tools and challenges in preventing conflict and negative uses of public space. Each city has identified its specific concerns related to public safety and urban security.

- Nice is primarily concerned about mass gatherings, incivilities, and increased aggressions against law enforcement officers, and has enacted legislative and regulatory measures to punish antisocial and criminal behaviours in public spaces.

- Rotterdam is also focused on the prevention of violent demonstrations, incivilities, and criminal activity in the online world, and has embraced the idea of administrative orders providing mayors with an instrument to sanction infringements on municipal codes of prohibitions.

- Riga is concerned about public order and public security in public spaces, with a particular interest in prevention of violent demonstrations, mass gatherings and crowds, incivilities, aggression against law enforcement, and protection of public spaces against modern technologies. Latvia has developed strong emphasis on supporting human resilience, with many law enforcement agencies working to guarantee the safety of individuals and society.

- Stuttgart is concerned about radicalisation and terrorism in relation to urban security, with a focus on religious radicalisation, hate speech, and discrimination towards certain groups. Germany has developed comprehensive legislation on this topic, with a recent focus on the problems that hate speech is causing for citizens, due to the rise of right-wing extremism.

- Turin is concerned about juvenile delinquency and crimes in public spaces committed by young people, with a specific interest in the phenomenon of “Baby Gangs.” The tools to be applied for urban security in this context should be oriented towards prevention and reintegration of delinquency by young people and not towards harsh punishment.

- Lisbon is concerned about crime committed in public spaces, in particular the problem of drug use on the streets. While most of the international and supranational legislation on the subject is directly related to drug trafficking itself, there is a lack of extensive legislative development at the national level to alleviate this problem, and the little legislation that does exist is not enforced by local authorities.

To study these topics, the national legal frameworks of the six cities were analyzed to assess the legal options and limitations of various legal tools, including:

- Nice: the Constitution, Criminal Code, and specific laws

- Rotterdam: the Constitution, Municipalities Act, Public Order Act, Police Act, and specific laws

- Riga: the Constitution, Criminal Law, Law on Police, Law on State Border, and specific laws

- Stuttgart: the Constitution, Criminal Code, Police Act, and specific laws

- Turin: the Constitution, Juvenile Code, and specific laws

- Lisbon: the Constitution, Penal Code, Municipalities Code, and specific laws

While each city has specific tools, mechanisms and legislation in place to address their urban security concerns, the main problem is the lack of initiative to implement legal recommendations or indications at the local level. National power should follow up and reinforce local authorities to implement action and prevention plans for crimes of concern to the actors.

Conclusion

The IcARUS legal report provides a critical analysis of the international and national legal frameworks for urban security policies in the six cities involved in the project. The analysis identified the most relevant instruments for each of the priority areas and the legal instruments available to the LEAs or municipalities in each city. The analysis also revealed the specific urban security challenges faced by each city and the legal instruments that are relevant for addressing these challenges. The report is expected to provide a comprehensive understanding of the required legal frameworks for preventive actions at the local level and the policies that are currently in place to prevent further criminal activities.

Including the gender perspective into urban security policies and practices

Including the gender perspective into urban security policies and practices

How to make cities safer for women, and how to integrate the gender perspective into all aspects of urban security policies and practices? This was the theme of a conference organised (online) by Efus for the IcARUS project, the first of a series of five.

Main takeaways

- create bonds between women/girls and men/boys and a sense of shared community

- think small: local, small-scale projects have a big impact

- include the perspective of women in data-collection tools and surveys

The idea that cities should be gender inclusive, i.e., take into account the specific needs of women, but also minority genders, is gaining traction all over the world. The World Bank and the United Nations recently published reports on this issue, and many universities, such as the London School of Economics, and researchers such as the renowned University of Oxford economist Kate Raworth, to name a few, are working on it.

Among all the aspects of urban life and development that affect women differently than men, security is one of the most prominent. All over the world, women and people from minority genders feel unsafe in some urban places because of the way they are designed and managed. For example, women are more likely to experience sexual harassment and gender-based violence, while men are more vulnerable to violence and robbery.

Integrating gender into urban security policies

This means that urban security strategies, policies and interventions, as well as their evaluation, should include the gender perspective in order to benefit both women and men and not reinforce inequalities. But how? This was the theme of the first of a series of five web conferences organised by Efus for the IcARUS project between January and September this year.

Delivered on 11 January, the conference was presented by Barbara Holtmann, Director of Fixed, a non-governmental “feminist organisation with a strong focus on women’s equity and safety” (in their own words) based in Johannesburg, South Africa. She is also an associate expert of Efus’ Women in Cities Initiative (WICI) and a member of the IcARUS Expert Advisory Board.

Rather than an ex-cathedra presentation, it was organised as a questions and answers session with representatives of five IcARUS partner cities: Lisbon, Nice, Riga, Rotterdam, and Stuttgart. (The sixth partner city, Turin, could not be represented at this event).

Lisbon: how to engage young people?

Within IcARUS, Lisbon (Portugal) has chosen to work on the issue of juvenile delinquency and has developed a 12-week programme to engage young people aged between 11 and 19 in community safety. How can they also engage them with the gender issue?

“Even though boys and men are the main cause of insecurity for girls and women, it is important to create a bond between them, a sense of shared community and empathy,” suggested Barbara Holtmann. “To do so, we can first ask girls and boys what security means for them. Also, we must look at what young boys can gain from the empowerment of girls, and how girls can be more empowered.”

Nice: what tools to reduce feelings of insecurity?

As part of IcARUS, the city of Nice (France) is working on how to improve feelings of insecurity. Research has shown that one factor in such perceptions is the feeling of being cut off from the rest of the city and isolated. At night, women feel more insecure than men. Are there tools to counter such perceptions?

One interesting avenue is to encourage small, very local projects by women, said Barbara Holtmann. She gave the example of a city in India that gave young local women a disused plot surrounded by buildings, which they converted into a thriving garden.

There are increasing numbers of mobile apps that help women find shelter and assistance when they feel threatened, in particular at night, such as Ask for Angela or Umay in France. “But the important thing here is that such complementary tools be integrated into a more global strategy against gender-based violence.”

“What women don’t do in a city because they fear for their safety doesn’t appear in crime statistics, but it’s an interesting way of creating an accountability framework for a municipality.” Barbara Holtmann, Director, Fixed and Associate expert, Efus’ WICI

Riga: improving data on feelings of insecurity

The Riga (Latvia) municipal police wants to better understand citizens’ feelings of insecurity and improve the quality of data they collect. The municipality is thus revamping its data collection system and will regularly gather feedback from citizens.

Barbara Holtmann suggested including the perspective of women in such tools. Also, an interesting point of view is to identify what makes them feel safe, rather than unsafe. She gave the example of the India-developed mobile application Safetipin, which maps out cities according to women-users’ safety ratings on issues such as public lighting, access, pavement and attendance.

“What women don’t do in a city because they fear for their safety doesn’t appear in crime statistics, but it’s an interesting way of creating an accountability framework for the municipality. Very often, crimes are the result of things that are beyond the mandate of cities, but here they can actually do something to create an environment conducive to women participating more fully and feeling less insecure.”

Rotterdam: gender and organised crime

One of the most pressing issues facing Rotterdam is organised crime, and the municipality has been working since 2014 on prevention programmes in an industrial park situated on the Spaanse Polder. The municipality is conducting different types of actions there and has set up processes to exchange and work with local stakeholders to prevent the spreading of illegal trafficking and business. How to link the issue of gender with preventing and fighting organised crime?

“The problem here is that we’re dealing with a business area, not a living one. However, women are also impacted by organised crime, not only as victims but also as family members of people who are engaged in it. So, one line of work is to communicate with mothers, sisters, daughters about the impact of organised crime on their lives, even if they’re not involved with it. This enables you to create another sphere of influence.”

Stuttgart: finding common ground

As part of IcARUS, the city of Stuttgart is working on the prevention of radicalisation leading to violent extremism, in particular among young people. More broadly, the city seeks to promote a sense of belonging to society among the young. How to also involve them in achieving gender equality?Amongst other initiatives, Stuttgart is contemplating proposing self-defence courses for girls.

“The problem is that if we train girls to defend themselves, we avoid tackling the main issue, which is that they shouldn’t have to defend themselves in the first place. The real question is rather how to make boys and girls feel they are part of the same group. What’s really important in gender issues is commonalities, rather than focusing on the difference.” > More information on IcARUS on Efus website

Conclusion

Gender is a crucial cross-cutting issue for IcARUS, and it will continue to be a significant area of focus in the future. With the introduction of WICI, Efus has expanded its expertise and support for gender-based approaches, methods, and tools, and is now providing its members with guidance on how cities and regions can better promote the inclusion of women in local security forces. As we move forward, it is important to prioritize gender-based perspectives and initiatives in the field of security to ensure that our communities are safe and inclusive for all.

IcaRUS Webinars Session 4- To what extent is restorative justice effective in juvenile deliquency cases?

During this session, representatives of the partner cities of the project (Rotterdam, Lisbon,

Nice, Stuttgart, Riga and Torino) will share their case-study and exchange with the expert

Tim Chapman, Chair of the board of the European Forum for Restorative Justice, on the

following questions:

- What are the main restorative justice models that may be applied for juvenile delinquency cases?

- What are the benefits of restorative justice for the judiciary system in juvenile delinquency cases, for adolescents and children as offenders, and for society?

- What are the requirements for a successful operation of restorative justice programmes for juvenile delinquency cases?

The 4th session of IcARUS web conferences “To what extent is restorative justice effective in juvenile deliquency cases?” will take place on May 17, 2023 at 2PM (CEST)

subscribe to be the first to receive icarus news!

Know what we've been up to and the latest on the European urban security frame.