Month: July 2022

Innovation meets Ideation in IcARUS workshops

The IcARUS Design Thinking workshops gathered a variety of stakeholders to develop innovative solutions that tackle urban security challenges

The IcARUS partners have been working over the past few months on building the foundations for designing and developing the project’s tools and practices. The six IcARUS partner cities laid the groundwork for the co-construction of urban security policies by launching the first Design Thinking Workshops with local stakeholders with the objective of designing innovative solutions to their urban security issues.

See the video of the methodology that was applied and read more, below, about the challenges addressed.

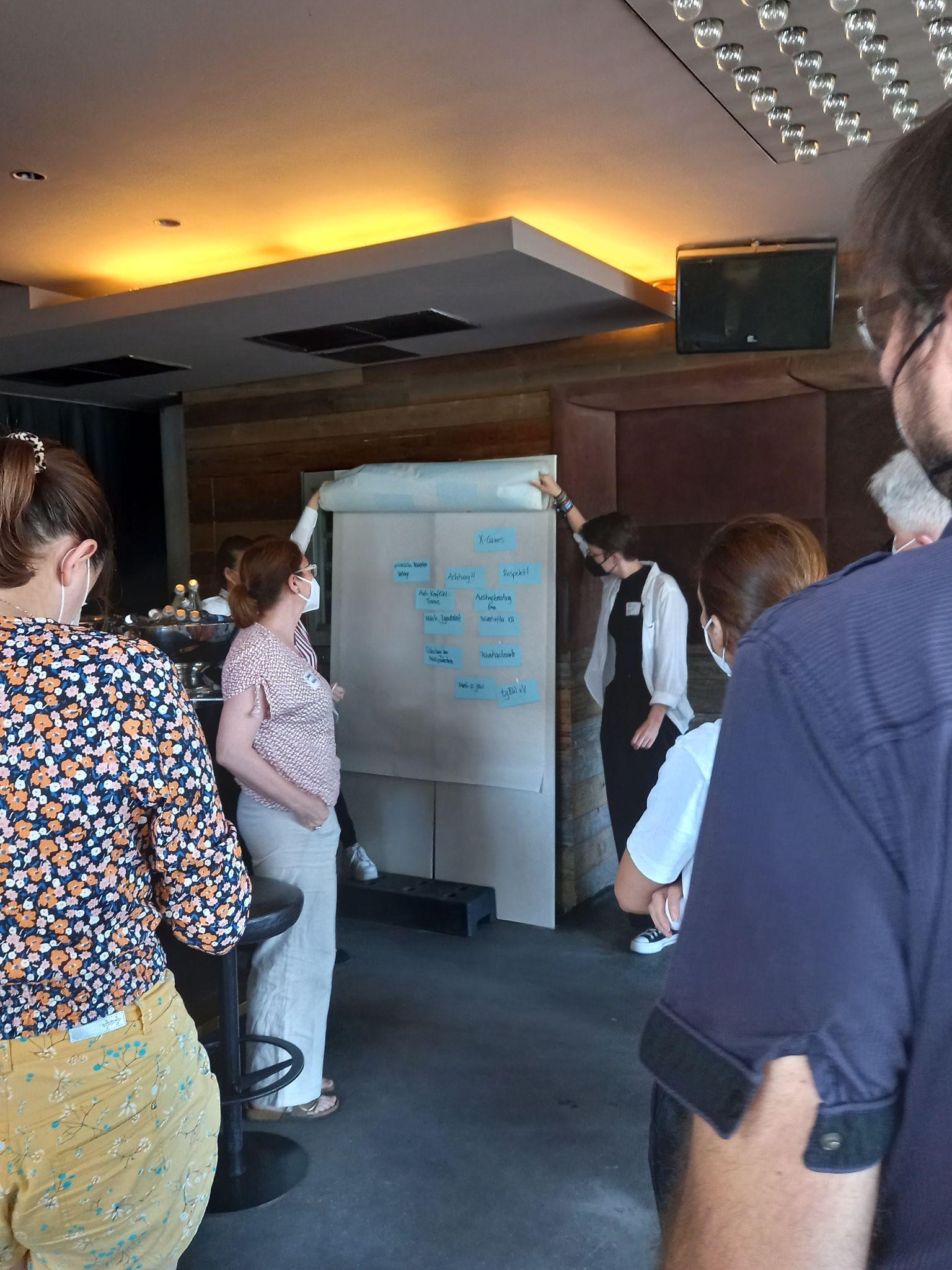

Using the Design Thinking methodology, the cities worked on identifying and defining their specific local issues and worked together with workshop participants to ideate concrete solutions. Each of the workshops included a representative sample of the local community, with attendees from civil society organizations, private sector companies, police and other local actors.

Based on the results of these workshops, the next step will be to redefine the problems and develop prototype tools to tackle them.

@Rotterdam organised their workshop on Safer Urban Spaces on 25 May

CHALLENGE: The Spaanse polder business park of Rotterdam, which is home to some 1,800 businesses and 24,000 employees, had long been somewhat neglected and had become a breeding ground for organised crime. Launched in 2014, the Holsteiner project seeks to restore order and reshape the landscape of this vast industrial estate. Despite some progress, a lot remains to be done. The challenge is to minimise the opportunities for crime but also to promote social cohesion within the industrial estate.

@Nice organised their workshop on Safer Urban Spaces on 8 June

CHALLENGE: The main challenge of the City of Nice is to strengthen feelings of security among residents of the Nice North district. Located in the heart of the city, this neighbourhood has two distinct areas, one rather well off and the other more working class. It is also a hub of activity and a buffer zone at the city’s point of entrance and exit.

The risk of burglary, which often increases during the summer, was identified as one of the root causes of residents’ feelings of insecurity. However, following exchanges with the local stakeholders that participated in the workshop, other root causes were identified, such as illicit trade, and in particular drug trafficking, as well as noise and crowdedness.

@Turin organised their workshop on Juvenile Delinquency on 14 June

CHALLENGE: The Turin Municipal Police has long been working on the prevention of juvenile delinquency by focusing on pre-adolescents and adolescents aged up to 18 as well as on young adults. Now, they are also working in close collaboration with NGOs targeting children in their first 1,000 days of life. This type of early prevention has become necessary with the emergence of what local media have termed ‘baby gangs’, or groups of very young people who gather spontaneously and are sometimes violent.

On top of the various measures taken, the challenge for the Turin Municipal Police is to deepen the understanding of juvenile group dynamics by collecting more data on the field. The City of Turin hopes that a better and deeper understanding of the youth violence phenomenon will help them design more efficient and effective prevention policies.

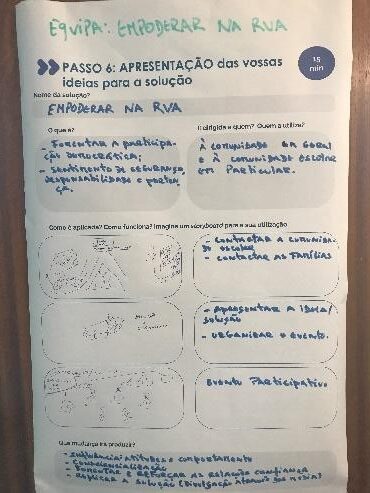

@Lisbon organised their workshop on Juvenile Delinquency on 20June

CHALLENGE: The City of Lisbon and the Lisbon Municipal Police seek to prevent juvenile delinquency and anti-social behaviour in a number of neighbourhoods where community policing teams work closely with local partners to jointly tackle security issues and improve residents’ perception of security. Notably, young people belonging to minority groups who grow up in socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods are at risk of following life patterns that lead to or perpetuate social exclusion in adulthood.

As part of the IcARUS project, the Lisbon Municipal Police are working on the prevention of juvenile delinquency and antisocial behaviour among the young and are developing a tool to promote safe behaviours and positive lifestyles (more info on the article here).

@Riga organised their workshop on Designing and managing safe public spaces on 29June

CHALLENGE: Once labelled ‘the crime capital of Europe’, the reputation of Riga, the largest city in the Baltic states, has significantly improved over the past decade. Today, it is a safe and vibrant city with a growing tourism industry, its Old City buzzing with cafes and restaurants. Most crimes and offences committed in the city are linked to the consumption of alcohol in public places, which is illegal. Recent initiatives to decriminalize it have been thwarted by conservative parties in Parliament.

@Stuttgart organised their workshop on Preventing Radicalisation on 5July

CHALLENGE: Although radicalisation leading to violent extremism is not an issue in Stuttgart, the city has had to deal with new ideological movements and actors that have emerged in the past two years in relation with the Covid-19 pandemic. Born in Stuttgart, the Querdenker movement has become nationwide, organising sometimes violent protests against Covid restrictions that have attracted widespread media attention. The state-level internal security agency, the Office for the Protection of the Constitution of Baden-Württemberg (Verfassungsschutz), has identified a growing radicalisation trend within the movement, with right-wing extremist and anti-government narratives gaining ground.

The city of Stuttgart has also been the theatre of serious riots involving hundreds of young people in June 2020, which spiralled into violence against police forces, vandalism and looting. Since then, more riots and revolts against police orders broke out in the city centre, albeit less serious.

Stay connected by subscribing to our Newsletter and social media and learn more about the Tools that will be developed!

IcARUS mid-term conference: harnessing 35 years of local policies and practices to design innovative solutions

Riga, Latvia, March 2022 – How can European local/regional authorities, practitioners and academics better work together to harness the wealth of knowledge acquired over three decades of local urban security policies and make our cities safer for all? This was the theme of the Efus-led IcARUS project’s mid-term conference, which gathered some 80 participants – local elected officials, security practitioners, academics, and civil society organisations – in Riga (Latvia) on 12-13 May.

Titled 35 years of local urban security policies: what tools and methods to respond to tomorrow’s challenges? the event marked the mid-point of the four-year project whose objective is to rethink, (re-)design and adapt tools and methods to help local security actors anticipate and better respond to security challenges.

A review of the knowledge base on urban security

Adam Crawford, Professor of Criminology at the University of Leeds, presented key findings of the state of the art review and inventory of tools and practices conducted by the project, looking back at 35 years of urban security research and practice.

Here are the main takeaways:

Research should also encompass implementation and cost-benefits

The focus of research on urban security is primarily placed on intervention mechanisms, outcomes and effects. Yet, some of the aspects which are of utmost importance for practitioners are not or barely reflected, notably implementation and cost-benefit.

Evaluation is important to inform accumulated learning, but practice evaluations are not yet thoroughly applied and there is also a lack of mainstreaming and sustaining good practices and successful interventions.

Adopting a multi-stakeholder approach from the onset

The implementation of problem-oriented approaches requires a change from the outset: instead of starting a multi-stakeholder collaboration after the problem has been defined by a single-agency organisational perspective (e.g. police) the multi-stakeholder approach must be implemented before to define the problem and include different perspectives.

Joining up academic research, policy-making and practice

The question of how to harness the knowledge on research and practice accumulated over the past 35 years was further developed in a panel session, which focused on how to strengthen and improve cooperation between research and urban security policies and practices.

Speakers noted that each category of urban stakeholders work on different time-frames and with a different finality: political decision-makers need results within the electoral cycle; researchers are not always aware of the constraints of both political decision-makers and practitioners on the ground, and the latter often find it difficult to collaborate with academics when implementing projects due to a lack of formalised cooperation structures. The panellists noted that mutual understanding between the different actors must be enhanced, which includes acknowledging the others’ different time-frames, needs and constraints.

A research-based approach in Mannheim

In the city of Mannheim, the Deputy Mayor introduced a research-based approach into urban security policy-making processes in order to inform the political debates in the city council and convey the importance of evidence-based urban security interventions and prevention.

Panellists and participants concluded that urban security stakeholders, whatever their specific field, must be able to innovate and even take risks, which means they all need to overcome a prevailing culture of blame and share both success stories and failures in order to learn and evolve.

Other takeaways

Other key topics explored by the IcARUS project were discussed during the day-and-a-half conference. Here are the key takeaways:

How to design inclusive and safe public spaces?

- Thedesign and management of public spaces must include end-users and their knowledge about their expectations and use of their local public spaces.

- Too often, public space security is presented through a negative lens (i.e. the risks and nuisance to be avoided), rather than a positive one (places where citizens can gather and express themselves, for example). We need to emphasise the positive and desired aspects of public spaces.

- The perspective of women, vulnerable groups and other users must be included from the outset, starting with the analysis or assessment phase.

Strengthening the resilience of young people

- We need to look at youth and see solutions rather than risks or threats. It is important to make people feel useful because they are often deprived of this opportunity.

- Developing resilience is increasingly seen as a valuable approach that works best when nurtured by wide local partnerships, which should include police (whether local or not).

- It is important to deconstruct stereotypes on both sides, i.e. the police and other public authorities on the one hand and local youngsters on the other.

Technology and urban security

- The design and use of technologies for security should be human-centred and take into account the specificities of each local context.

- ● Among the ‘human values’ to be incorporated in any urban security technology deployment are: human welfare, trust and privacy.

- A valuable tool for an ethical use of technology is the EU Regulatory Framework on Artificial Intelligence (April 2021), which defines the level of acceptability of a range of technologies and uses (from minimal to unacceptable risk).

Challenges of prevention in a changing landscape of radicalisation

- As the level of governance closest to citizens, local authorities are best placed to prevent radicalisation by enhancing social cohesion and mobilising local partners and networks to this end.

- In the past few years, our democratic societies have seen anti-democratic leaders come to power in some countries. Authoritarianism and anti-democratic extremisms are moving closer to the centre of society.

- Polarising and divise narratives that attempt to undermine democratic principles are increasingly spread by actors who are members of the social and economic elite and use the anger created by social exclusion to feed their own agenda.

- It is crucial to adapt local prevention strategies to respond to these evolving dynamics and new realities of radicalisation.

> More information about IcARUS

> The minutes of all the conference sessions will be shortly available on Efus Network (members only)

Lisbon IcARUS Local Workshop – “Help create innovative solutions for your city!”

The IcARUS Local Workshop brought together partners from the Community Policing of Lisbon, to reflect on solutions to promote safety behaviours among the young. The Community Policing model in Lisbon, developed by the Lisbon Municipal Police with local partners, aims to promote preventive strategies that contribute to the improvement of safety and well-being of the community.

One of the main concerns security partnerships address is that young people, especially those living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, are often exposed to risk factors such as poverty and social exclusion, following life course patterns leading to social exclusion in adulthood as well. Policing in these disadvantaged neighbourhoods requires community policing officers the skills to interact with young people in a positive and not repressive way, to be able to foster positive relationships between police and young people. Also, working in partnership with key stakeholders (e.g. social workers, schools, youth services, and residents associations), enables the police to tackle problems from innovative perspectives, and consequently, improving the efficacy of the strategies to reduce situations of crime, antisocial behaviour in public space and feelings of insecurity.

In IcARUS project, the Lisbon Municipal Police addresses the topic of Preventing Juvenile Delinquency, with the challenge to reduce antisocial behaviours in youth and develop a tool to promote safety behaviours and positive lifestyles. The goal is to build together with partners, a new preventive tool.

The workshop, held on June 20, had more than 50 participants from the network of the Lisbon Community Policing as well as civil society and entities working in the prevention field, with extensive knowledge and intervention experience. This multidimensional engagement of stakeholders is essential for creating a relevant and quality solution during the IcARUS Project. The workshop coordinated by the Lisbon Municipal Police Team, followed a Design Thinking methodology with participants working in teams. This layout helped promote the exchange of ideas among participants for the new preventive tool. During the workshop, most of the ideas for solutions focused on the involvement and active participation of young people in the process. Several ideas were discussed and presented for the construction of solutions that foster youth empowerment and their connection to the community, to feelings of community belonging and ownership of their life project. The unpreparedness of adults to deal and work with youngsters was also highlighted several times as a constraint. To know how to listen to young people and the capacity to involve them in the construction and delivery of solutions to their present and future were pointed out as key competencies to successfully work with youth. Also, was stressed the importance of providing access to experiences and positive references that promote youth civic participation and value the potential of young people, their skills and talents, enabling them to adopt positive behaviours.

The inputs and materials resulting from the Workshop will be analysed by the IcARUS consortium. The elaboration of conceptual proposals for the design and creation of a prototype of the preventive tool will be developed in the next months. This prototype will be presented at the second local workshop of the project, scheduled for the first quarter of 2023, where once again community policing partners will be engaged to share their feedback and suggestions for improvement of the prototype proposal. In the meantime, the challenge of involving and empowering young people for positive and civic participation will also be continued in the daily work of the community policing partnerships in the city.

IcARUS mid-term conference: harnessing 35 years of local policies and practices to design innovative solutions

Riga, Latvia, March 2022 – How can European local/regional authorities, practitioners and academics better work together to harness the wealth of knowledge acquired over three decades of local urban security policies and make our cities safer for all? This was the theme of the Efus-led IcARUS project’s mid-term conference, which gathered some 80 participants – local elected officials, security practitioners, academics, and civil society organisations – in Riga (Latvia) on 12-13 May.

Titled 35 years of local urban security policies: what tools and methods to respond to tomorrow’s challenges? the event marked the mid-point of the four-year project whose objective is to rethink, (re-)design and adapt tools and methods to help local security actors anticipate and better respond to security challenges.

A review of the knowledge base on urban security

Adam Crawford, Professor of Criminology at the University of Leeds, presented key findings of the state of the art review and inventory of tools and practices conducted by the project, looking back at 35 years of urban security research and practice.

Here are the main takeaways:

Research should also encompass implementation and cost-benefits

The focus of research on urban security is primarily placed on intervention mechanisms, outcomes and effects. Yet, some of the aspects which are of utmost importance for practitioners are not or barely reflected, notably implementation and cost-benefit.

Evaluation is important to inform accumulated learning, but practice evaluations are not yet thoroughly applied and there is also a lack of mainstreaming and sustaining good practices and successful interventions.

Adopting a multi-stakeholder approach from the onset

The implementation of problem-oriented approaches requires a change from the outset: instead of starting a multi-stakeholder collaboration after the problem has been defined by a single-agency organisational perspective (e.g. police) the multi-stakeholder approach must be implemented before to define the problem and include different perspectives.

Joining up academic research, policy-making and practice

The question of how to harness the knowledge on research and practice accumulated over the past 35 years was further developed in a panel session, which focused on how to strengthen and improve cooperation between research and urban security policies and practices.

Speakers noted that each category of urban stakeholders work on different time-frames and with a different finality: political decision-makers need results within the electoral cycle; researchers are not always aware of the constraints of both political decision-makers and practitioners on the ground, and the latter often find it difficult to collaborate with academics when implementing projects due to a lack of formalised cooperation structures. The panellists noted that mutual understanding between the different actors must be enhanced, which includes acknowledging the others’ different time-frames, needs and constraints.

A research-based approach in Mannheim

In the city of Mannheim, the Deputy Mayor introduced a research-based approach into urban security policy-making processes in order to inform the political debates in the city council and convey the importance of evidence-based urban security interventions and prevention.

Panellists and participants concluded that urban security stakeholders, whatever their specific field, must be able to innovate and even take risks, which means they all need to overcome a prevailing culture of blame and share both success stories and failures in order to learn and evolve.

Other takeaways

Other key topics explored by the IcARUS project were discussed during the day-and-a-half conference. Here are the key takeaways:

How to design inclusive and safe public spaces?

- Thedesign and management of public spaces must include end-users and their knowledge about their expectations and use of their local public spaces.

- Too often, public space security is presented through a negative lens (i.e. the risks and nuisance to be avoided), rather than a positive one (places where citizens can gather and express themselves, for example). We need to emphasise the positive and desired aspects of public spaces.

- The perspective of women, vulnerable groups and other users must be included from the outset, starting with the analysis or assessment phase.

Strengthening the resilience of young people

- We need to look at youth and see solutions rather than risks or threats. It is important to make people feel useful because they are often deprived of this opportunity.

- Developing resilience is increasingly seen as a valuable approach that works best when nurtured by wide local partnerships, which should include police (whether local or not).

- It is important to deconstruct stereotypes on both sides, i.e. the police and other public authorities on the one hand and local youngsters on the other.

Technology and urban security

- The design and use of technologies for security should be human-centred and take into account the specificities of each local context.

- ● Among the ‘human values’ to be incorporated in any urban security technology deployment are: human welfare, trust and privacy.

- A valuable tool for an ethical use of technology is the EU Regulatory Framework on Artificial Intelligence (April 2021), which defines the level of acceptability of a range of technologies and uses (from minimal to unacceptable risk).

Challenges of prevention in a changing landscape of radicalisation

- As the level of governance closest to citizens, local authorities are best placed to prevent radicalisation by enhancing social cohesion and mobilising local partners and networks to this end.

- In the past few years, our democratic societies have seen anti-democratic leaders come to power in some countries. Authoritarianism and anti-democratic extremisms are moving closer to the centre of society.

- Polarising and divise narratives that attempt to undermine democratic principles are increasingly spread by actors who are members of the social and economic elite and use the anger created by social exclusion to feed their own agenda.

- It is crucial to adapt local prevention strategies to respond to these evolving dynamics and new realities of radicalisation.

> More information about IcARUS

> The minutes of all the conference sessions will be shortly available on Efus Network (members only)

State of the Art Review and Key Lessons

Work Package 2: Task 2.1

Introduction

The IcARUS State of the Art Review has now been completed and submitted to the Commission. It represents an extensive understanding of the accumulated knowledge base on European urban security over the past 30 years, highlighting key lessons, trends and issues and provides an assessment of the research literature. Here, we present some of the main findings relating to the Review’s four focus areas. Over forthcoming weeks, a variety of factsheets and useful resources to communicate the findings to diverse audiences will be produced. It is intended that these will inform subsequent work of IcARUS and urban security practices across Europe.

The Review and Key Lessons

This Review constitutes an analysis and assessment of the academic research literature relating to crime prevention and urban security topics, and was supplemented by interviews with International Research Experts and interviews with representatives from the six IcARUS partner cities. The focus was on reviews of interventions including summaries and evaluations of multiple interventions, rather than evaluations of individual programmes. It was limited to the English language, representing a broad overview of the current state of crime prevention as urban security. Here, we provide the most prominent lessons from the four focus areas.

The Urban Security Knowledge Base

- Despite considerable advances over the last 30 years, the urban security knowledge base lags behind other fields of public policy.

- Nonetheless, the knowledge that has been accumulated is not being sufficiently implemented or applied in practice.

- Urban security interventions are:

- Often poorly informed by research evidence base (where it exists);

- Rarely specify the theories of change (mechanisms) intended to achieve the desired outcome;

- Frequently suffer from implementation failure;

- Rarely involve rigorous evaluation allowing lessons to be learnt.

The Evidence Base

- The focus on ‘what works’ has provided some rich insights but also reduced the scope of evidence and restricted the methods of data collection.

- It has tended to imply (or been taken to imply) ‘off the shelf’ universal solutions.

- Greater regard needs to be accorded to the relational and process-based mechanisms that foster change.

- Evaluation is important for accountability, to strengthen institutional development and to inform accumulated learning.

- Evaluation needs to be built into interventions in ways that inform understanding of what works, where, for whom and under what conditions.

- In measuring urban security outcomes, police recorded crime data alone are insufficient.

- Different types of data need to be gathered from and shared between institutions.

Preventing Juvenile Delinquency

- Early intervention and developmental programs are increasing in popularity and have proven to demonstrate success. These programs can prevent harmful activities before they occur or behaviour escalates and have also fostered a focus on breaking inter- generational cycles of behavioural problems, violence and abuse and targeting whole families for intervention and support.

- Multi-risk component interventions targeted at multiple risk factors appeared to be more successful than single-factor interventions.

- There was a general lack of research that considers measures relating to the progression of juvenile delinquent acts or behaviours, and implications for future engagement with the criminal justice system (i.e. long-term assessments, context-specific measures, longitudinal studies).

- There remain enduring tensions between universal as opposed to targeted (risk-based) interventions, given concerns about stigmatisation and the potential labelling effects of targeted approaches.

Preventing Radicalisation Leading to Violent Extremism

- Using resilience as the foundation for an integrated framework of prevention appears to show promise due to its holistic approach and wide applicability. However, currently there is little rigorous empirical evidence to support interventions focusing on resilience and, consequently, more empirical evidence is needed.

- Developing inclusive and community-focused programmes ensures broad applicability, mindful of and suited to the local context.

- For primary prevention programmes in educational settings and open youth work to be successful and not counterproductive evidence highlights the need to:

- Ensure integration of all minorities;

- Equip students with tools to learn critical thinking, rather than focusing on a particular ideology or cause;

- Empower students with ways in which they can actively participate in the democratic process;

- Clearly define core values (e.g. democracy, human rights);

- Provide a safe space for exploration and discussion without the fear of referral to authorities.

Preventing and Reducing Trafficking and Organised Crime

- The dominant approaches to organised crime and trafficking remain ones focused on law enforcement through policing, prosecution and punishment, however given their limited effectiveness as prevention strategies, some municipalities have increasingly deployed a variety of administrative measures and ordinances with some success.

- Research suggests a need to examine and understand the underlying drivers facilitating the trafficking of human beings – i.e. contributing industry sectors, to target responses – and to foster policies promoting inclusion and integration of marginalised communities, reducing their dependence on crime and the illicit economy.

- Studies highlight the importance of multi-agency partnerships and inter-agency cooperation. Holistic responses are required to address the inherent complexity of the phenomenon of organised crime and trafficking. These are enhanced where a clearly defined framework of responsibilities and accountability between partners is adopted. Ineffective partnerships and a lack of information sharing are the most common reasons for implementation failure.

Design and Management of Safe public Spaces

- Interventions at the design stage enable up-stream, early opportunities to affect security and harm reduction outcomes, rather than retro-fitting changes after the event.

- Human-centred design solutions afford sensitivity to local context, a focus on the nature of the problem(s) to be addressed, an understanding the causes of social problems, the nature of social interactions and the ways in which people use and adapt to solutions/interventions.

- Involving communities (or representatives) in the design of interventions creates a sense of (local) ownership and participation, as well as ensuring local context is accounted for and incorporated.

Further Dissemination

We look forward to producing numerous outputs from this Review in the coming weeks, including factsheets and videos which will be available on the IcARUS website. These are intended to be easily accessed by a wide audience and will focus on specific areas of interest or prominence within the Review. Additionally, the State of the Art Review will also be publicly available soon on the IcARUS website, for those interested in reading the full detail and extent of the Review.

subscribe to be the first to receive icarus news!

Know what we've been up to and the latest on the European urban security frame.